Sichuan Authorities Announce Shift to Chinese Language Instruction

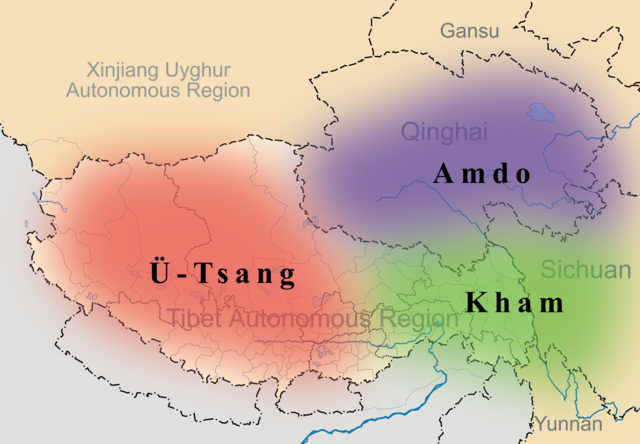

In early April, schools in Ngawa [Ch.: Aba] prefecture, a largely Tibetan region of China’s Sichuan province, reopened following the Covid-19 outbreak. The good news came with a disturbing development: the use of Tibetan language in classes would be scrapped as of September, when the next academic year begins.

Last month, Human Rights Watch detailed that threat in primary schools in Tibetan areas of China: the gradual replacement of Tibetan-language instruction with the “national” language. We noted signs of regional variation in the implementation of this policy, including a September 2018 reaffirmation of the use of Tibetan language in primary education passed by the People’s Congress in Ngawa. This distinction, however, has now proved overly optimistic.

Tibetan netizens, despite rigid police surveillance and the prospect of reprisals, took to social media to express disbelief and anger. In lengthy, eloquent WeChat posts, school and university teachers – all graduates of the schools now at risk – scathingly dismissed official justifications that Tibetan language is inadequate to teach science subjects and that graduates of Tibetan-led schools perform poorly in exams.

The teachers explained that Tibetan medium-teaching has benefits the authorities are ignoring: Tibetan-medium students scored above average in exams to qualify for higher education, and were highly motivated, while Chinese-medium students in their area rarely got as far as middle school. “This decision…will achieve nothing other than turning Tibetan students into fools with a mediocre grasp of the Chinese language,” wrote one.

“It will turn future Tibetan students into parrots, rather than fluent speakers of both languages,” said another. “Officials at county level and above [those unsympathetic to Tibetan culture] don’t send their kids to these schools [preferring more prestigious ones in urban areas of the mainland],” he continued, “yet now they insist that rural Tibetans do.”

At a time of deepening government repression, and assimilationist policies targeting supposedly “autonomous” minority peoples in China, these changes trigger many Tibetans’ deepest fear – that of losing the ultimate guarantee of their distinct identity, their spoken and written language.