Hong Kong’s promised freedoms are now in danger, as the ruling Chinese Communist Party imposes a draconian security law on the city and the local authorities announce sweeping new powers to enforce it, according to a journalists’ group.

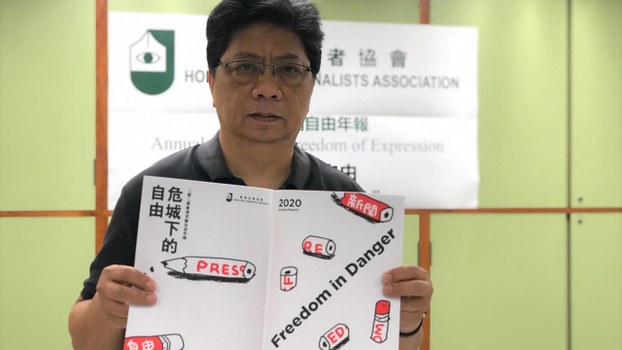

“There may be a mass drain of capital and a new wave of migration,” the Hong Kong Journalists’ Association (HKJA) said in an annual report released on Tuesday. “The city is in danger. People fear a loss of their freedoms.”

The report said Hong Kong now looks set to pay a “huge economic and political price” as police are given powers to order online service providers to take down content deemed problematic under the law, and to require organizations to hand over details of their sources.

“Hong Kong is entering into turbulent waters. Beijing will resort to harsh legislation, more direct interference and behind-the-scenes arms-twisting,” the report predicted.

“The police will intensify [their] use of force and tougher tactics to handle protesters,” it said, adding that the media have a duty to monitor and report on the law’s implementation, and the actions of those in power.

“They will be confronted with more suppression from the central government and Hong Kong government and the pro-establishment camp,” the report said, adding: “Hong Kong is now a city in danger.”

Under the national security law, which was imposed on Hong Kong on June 30 by decree from Beijing, the media will become an immediate target, the HKJA said.

“Any reports and commentary that oppose the authorities could fall into the trap of the national security law,” it said.

“A lot of journalists [are] deeply worried about their future and that they may become the victim of misfortune,” the report said.

“A news programme or a commentary article could become … evidence in the [prosecution] of national security offenses,” it said. “Journalists may be forced to keep silent, worsening the chilling effect on media freedom.”

The HKJA said the past year has seen a huge increase in police violence and obstruction of journalists trying to do their jobs, especially those reporting from the front lines of the anti-extradition movement that broadened into a mass campaign for fully democratic elections and police accountability.

Off limits for discussion

HKJA chairman Chris Yeung said stories about corruption among high-ranking police officers or interviews with former British colonial-era officials could all become off-limits under the new law, which outlaws anything likely to “cause Hong Kong residents to have misgivings” about the authorities.

“The current climate is such that people could be too afraid to speak [to the press],” Yeung told RFA.

He said new implementation rules taking effect on Tuesday would allow police to issue takedown notices to online content providers, and could compromise journalists’ ability to protect their sources.

“If these rules are used, it will be to ask media organizations and journalists to assist police with their investigations by asking for phone call transcripts or other relevant material,” he said. “In the past, if they wanted to search [a property] for journalistic material, they had to go to a court [to apply for a warrant].”

“Now there are no checks and balances, what option would journalists have but to comply? No, we couldn’t think of one either,” he said.

Platform and internet service providers are covered by the rules, and Facebook and WhatsApp said on Monday they had “paused” the processing of government requests for user data in Hong Kong.

The encrypted messenger Telegram, once widely used by the pro-democracy movement, also said it had ended cooperation with police and government in Hong Kong.

The National Security Law for Hong Kong bans a vaguely defined and all-encompassing slew of actions including many seen during last year’s pro-democracy protests and anti-extradition movement.

The law targets anyone in the world committing actions within its scope, regardless of whether they live in Hong Kong or are its permanent residents.

Anyone suspected of “crimes” under the law can be issued with a travel ban, with their passport confiscated and their assets frozen.

Under the implementation rules, warrantless searches of people’s homes may be authorized by a police officer carrying the rank of assistant commissioner, while “less intrusive” covert surveillance of suspects under the law can be authorized by a directorate-level police officer.

Reported by Man Hoi-tsan for RFA’s Cantonese Service. Translated and edited by Luisetta Mudie.

Source: Copyright © 1998-2016, RFA. Used with the permission of Radio Free Asia, 2025 M St. NW, Suite 300, Washington DC 20036. https://www.rfa.org.