An academic conference held at George Washington University – of excellent scientific level and meaningful participation from the public – illustrates and confirms the nightmare that Xinjiang lives daily, where religion is a “pathology” and a whole people is subjected to “rectification” because it is “wrong.”

Marco Respinti

While much of the planet continues to ignore what happens every day in China, the academic world (or at least a significant part of it) asks the international community to save the ethnic minorities and religions persecuted in that great Asian country. A special light on the severe situation afflicting the “autonomous” region of Xinjiang has been aptly lit by the Symposium on the mass incarceration of Uyghurs in China, organized and coordinated in Washington, D.C. by Sean R. Roberts, a cultural anthropologist at the Elliott School of International Affairs (ESIA) of the George Washington University (GWA). The part of the Central Asia Program of the GWU’s Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies of the conference was held on Tuesday, November 27, in the Lindner Family Commons of the ESIA.

On the eve of the conference, November 26, Roberts and several of his colleagues scheduled to speak at the event the following day conducted a significant press conference at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., to denounce ‒ with no fear for their career, as they have stressed ‒ the repression in Xinjiang with the launch of a statement signed by 278 scholars from 26 countries and multiple academic disciplinescalling for the immediate cessation of all forms of coercion and harassment implemented by the central and regional government of China against the Uyghurs.

Now, it does not happen every day to see expert scholars and tough men shed their tears in front of journalists and cameras. But this is what happened on Monday when, helped by an interpreter, Mihrigul Tursun, a 29-year-old Uyghur, took the microphone ‒ also in tears. She ended up in a nightmare that has marked her body and soul forever after one day she decided to go to Egypt to study English and thus got caught in a vague, unfounded accusation of espionage. She and her three young children (one of whom died) have been abused in every imaginable way. She has been incarcerated in literally inhumane conditions, forced to endure the violence of all kinds and compelled, along with her children, to take unknown medicines. Thanking the United States for giving her the opportunity to live in a free country where she can be an Uyghur and live her Muslim faith without fear, the young woman closed her testimony with two appeals. The first was addressed to the United States, asking that they never leave the Uyghurs alone, people persecuted only because of their ethnicity and faith. The second appeal was to anyone who would happen to travel to China: to ask the question “Where are my mother and my father?” on her behalf.

DNA and the Third Reich

The Tuesday conference, divided into three panels, proved to be an example of authentic academic excellence: dense and high-level presentations that documented, even with details collected through field trips, what happens in a region removed from the collective imagination.

In the first panel, Documenting the “Re-education Camps,” the speakers were Timothy A. Grose, a sinologist of the Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology in Terre Hauste, Indiana; Seiji Nishihara, an economist at the International University of Kagoshima, Japan; and Sophie Richardson, director of the China Department of Human RightsWatch.

Prof. Grose focused on the use, by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), of a medical language to stigmatize as pathology the “terrorism” and “religious extremism” that the CCP attributes to Uyghurs. In fact, for the CCP, to be Uyghurs and to aspire to freedom is tantamount to being terrorists (i.e. the arbitrary definition that the Party gives of “terrorism”), while the Beijing government labels any manifestation of religious identity as “religious extremism,” from simple personal prayer to the ostentation of sacred symbolism, for example, on garments or public signs. The very fact of being Uyghur (an ethnic group that almost coincides with the faith) is not only a crime but also a disease, since “terrorism” and “religious extremism,” in the communist sense, are two sides of the same coin. Thus, Uyghurs are being cured ‒ and this is exactly what the CCP’s “civilizing mission” offers to do. In this treatment, the limitation of contagion and the cauterization of open wounds are included: that is to say, open persecution, managed propagandistically as a measure of national hygiene.

Prof. Nishihara then did what none had dared before – to thrust the knife into the wound. Why does the CCP, more or less rhetorically Nishihara asked himself, try to find alternative names to its “re-education” camps, ridiculously referred to as “vocational training” centers? Because it tries in every way to avoid to call them what they really are, that is concentration camps, and this for the simple reason that such definition recalls German National-Socialism and its systematic extermination of millions of innocents. Yet, the reality of Chinese camps is, in many respects, identical to those established by the Third Reich: the same contempt for the human person and the same arbitrariness. But a point makes them really similar. It is not true that the Uyghurs, says Nishihara, are persecuted because they are separatists. Maybe some of them are too, but the reason why the CCP smashes them is just because they are Uyghurs, i.e., bearers of a “different” cultural and religious identity, and therefore intolerable to the regime. Many cases illustrate this well, but a particular example demonstrates it brilliantly: the case of three intellectuals, Satar Sawut (former director of the Xinjiang Education Supervision Bureau), Yalqun Rozi (writer and literary critic), and Tashpolatt Teyip (former president of Xinjiang University), who disappeared last year because they were critical to the latest repressive developments even though they were loyal to the CCP and, therefore, not at all separatists.

Prof. Richardson then brought the attention to another nodal issue. The system that the CCP uses to control exiles even abroad, a problem that refugees suffer cogently and live with enormous fear. The Beijing regime employs sophisticated technology, for example subjecting those who request a passport to DNA sampling in order to map “dissent.” After all, Richardson asks, to whom refugees can appeal when the CCP orders them, in foreign countries, to repatriate immediately or serious trouble will come for them and their families? How can they respond?

“Paternalism” and the diaspora

During The second panel, Impact of the Camps on Uyghur Communities, those who gave presentations were Joanne Smith Finley, a sinologist at the University of Newcastle in Great Britain; Darren Byler, an anthropologist at the University of Washington; Elise Anderson, an ethnomusicologist at the Indiana University in Bloomington; and Dilnur Reyhan, a specialist of the Uyghur diaspora at the Institut national des langues et civilisations orientales in Paris.

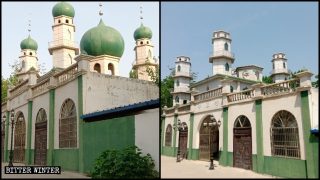

Prof. Finley offered first-hand impressions of the complete change that occurred in the Xinjiang society due to the recent recrudescence in the repression of that region’s inhabitants, a region which lives in fear and is distressed by uncertainty. Reconnecting with Prof. Grose’s presentation, Finley underlined the psychiatric approach to the problem of religion used by the CCP, which treats the faithful as alienated to be rendered harmless and to be corrected. Her speech has also touched on the taboo that no one dares to cite, but of which there is a lot of great evidence: the ethnic and cultural genocide that is deceiving Xinjiang. A crucial concept introduced by Finley is that of “fear of the mosque”: that is to say the “sacred” terror that the CCP feels towards everything that even remotely recalls the faith of the Uyghurs, which is to be eradicated with a forced secularization of customs and traditions that needs to be de-sacralized and sinicized.

On the same wavelength, Prof. Byler documented the “re-educational paternalism” implemented by the regime in the Uygur region. Human Rights Watch estimates that about 10% of Uyghurs are currently held in “re-educational” concentration camps. Millions of people are then subject to “rectification” and a million government officials, as Bitter Winter has documented, are employed in monitoring ethnic Muslims. In short, the state functions as an Orwellian “Big Brother, which, with the excuse of national security, suffocates society and religious beliefs through an increasingly strict and effective control.

Prof. Anderson then continued on not dissimilar tones, illustrating how this “paternalism” is expressed in an exemplary way in the imposition of an art ‒ music ‒ which apparently pretend to be traditional, but which instead only aims, through a continuous bombardment of society, to empty identitarian music of any meaning and to rectify it according to the ideological slogans of the Party, which in this way penetrates surreptitiously into society. Another call of hers has been particularly significant. The Uyghur language, the sign of the identity of an entire people, will disappear. The new generation says the specialist, has virtually no poets, ubiquitous custodians of the language, and this fact will end up working for the CCP.

The presentation of Prof. Reyhan was relevant since it has illustrated the deep divisions in the groups of the Uyghur diaspora in the West, which often undermines their initiatives. The fault runs mainly on the front of independence, dividing those who openly invoke it from those who are primarily interested in other issues, speak only, sometimes generically, of autonomy, but, above all, of human rights and religious liberty. Obviously, the situation is exploited by the CCP, which defines all Uyghurs, specifically making no distinctions, as separatists, and therefore as terrorists.

Biopolitics and Bitter Winter

The third panel, Contextualizing the Re-education Camps, featured James A. Millward, an historian at the Georgetown University in Washington; Sandrine E. Catris, an historian of Augusta University, Georgia; Roberts of the GWA; and Michael Clarke, a researcher at the Australian National University of Canberra, an expert on Xinjiang history and society.

Prof. Millword chose an original topic. The empires, supranational entities by definition, he said, have always been able to deal with cultural, linguistic and religious pluralism effectively. Of course, the historical empires have all been different, one from the another, but they have, nonetheless, favored an undoubtedly undemocratic social composition by modern standards, yet objectively functional. The nation-states, which by definition are the negation of empires, have instead never been able to deal with the problem adequately: suffering from endemic nationalism, they rather have always exacerbated it. From an indeed not nostalgic point of view, Millword affirms that this question is constantly re-emerging. Today’s China has inherited an empire, but it has turned it into a large nation-state, in which nationalism, in the form of sinicization, has transformed socialism into an even greater nationalist problem.

The parallel between the regime of Xi Jinping and the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) promoted by President Mao Zedong (1893-1976) has been effectively illustrated by Prof. Catris, who highlighted the existing parallels between those two historical phases in forced education, the assimilation of minorities, harsh repression alternated with attempts to domesticate religions, mass incarcerations, use of forced labor and the loyal fidelity to the Party line, no matter what, which is a requirement for everyone. There are a few differences between then and today, but perhaps, since very few speak of it, today is even worse than then.

Prof. Roberts then illustrated the terrorist accusation systematically moved by the CCP to the Uyghurs. Recalling the need to deepen the very notion of “terrorism,” in meticulously adjusting it according to specific cases and, thus, inviting everyone to always distinguish rigorously between groups, political propaganda and historical reality, the anthropologist used the category of “Biopolitics” elaborated by the French philosopher Michel Foucault (1926-1984) to point out the very spacious and dangerous equation made by the CCP. For the Beijing regime, being terrorists is the same as being sick; but the sick are, first of all, religious people; therefore being affected by the disease of “religious extremism” is equivalent to being terrorists. It is a Moebius tape functional to the loop of the “ideological apostolate,” which Westerners often take uncritically for real (making, thus, themselves accomplices of the CCP’s crimes) and that Xi Jinping uses to repress millions of non-violent people brutally.

Lastly, Prof. Clarke brought attention to the causes of the new, recent repressive wave, asking “Why now?” His answer is a combination of causes that have to do with geopolitics, security, and economy. Physically standing in front of China’s westward march, Beijing sees Xinjiang as an indispensable part of Chinese public safety and national security (like Tibet), as well as a new market for the country’s over-productivity. But, says the CCP, Xinjiang’s customs and faith must be rejuvenated since they restrain modernization, which is useful to transform it into a new, enormous plaza for consumption. And then, given that China is somehow trying to export its own repressive “security package,” the great experiment of social engineering implemented in Xinjiang is a strategic showcase.

Ended by a lively roundtable animated with questions from the audience ‒ among which also sat Rebyia Kadeer, the historical, moral leader of the Uyghur world ‒ the conference demonstrated an undeniable reality. The truth about the Chinese communist repression is well known, solidly documented and perfectly understood, even in the details, by scholars. As always, however, civil society, mass culture, and even politics stay behind.

Bitter Winter was born and exists to help bridge this gap between specialists and public opinion, continually looking for ways to link these two worlds, which, in many ways, live distant lives. The fact that all the speakers at the Washington Symposium and also a substantial part of the audience appeared to know, appreciate, and also occasionally use Bitter Winter, welcoming the fact that it often publishes news that one cannot find elsewhere, always documented and certified, it is a factor of great importance. Not for parochialism, but as a confirmation of the fact that what we are doing here every day, at the cost of enormous risks for many our reporters and contributors, is what it is needed to do.