Cultural Revolution technique revived from the 1960s pits masses against masses, brother against brother, faith against faith, to control belief.

In November, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leaders from the central and provincial levels held a conference in the city of Shaoxing in the eastern coastal province of Zhejiang. The conference bore the enigmatic title, “A Commemoration of the Expansive Study of the Fengqiao Experience on its 55th Anniversary.” Immediately afterward, official Party media published a series of articles commending the Fengqiao Experience, contributing to widespread momentum for the project.

This promotion of the so-called Fengqiao Experience has caused serious concern among many people with historical memory because it revives ghosts from the Cultural Revolution.

The Fengqiao Experience is a Mao-era method for using massed groups of citizens to monitor and reform those who are labeled as “class enemies.” The method operates on the principle that “Ten people work together to reform one person so that conflicts are not handed over to higher authorities and thus the society is reformed from within.” In colloquial terms, this is mobilizing the masses against the masses.

The Fengqiao Experience was the pilot program of Chairman Mao’s nationwide Four Clean-ups Movement (to cleanse politics, the economy, organizations, and ideology), the experience of comprehensive management of public order originally implemented in the 1960s in Fengqiao district, in Zhejiang province. The area is today known as Fengqiao town.

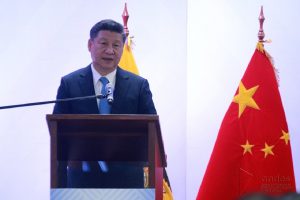

More recently, in 2013, Xi Jinping ordered that Party and government departments at all levels become familiar with the significance of the Fengqiao Experience, and carry forward this “good tradition.” In its modern iteration, this method of mass control and punishment has been used to suppress and reform dissidents and religious groups.

The Fengqiao technique in action is extremely effective. Take, for example, an incident in Wendeng city, in the eastern and coastal province of Shandong. In March, three villagers in their seventies from a Christian house church were summoned repeatedly to a public meeting space of the village to undergo “struggle sessions.”

They were ordered to stand in the center of the meeting area, in the presence of all the town officials. The village secretary, the director of the village’s All-China Women’s Federation (under the direct supervision by the CCP, the organization was founded in 1949 to support the Party and promote women’s rights) and others took turns to question the villagers’ religious beliefs in order to “educate them through criticism.” The believers were criticized for their faith in God, which was deemed as superstitious, as their opposition to the government, and as usurpation of political power.

The villagers were ordered to abandon their religious beliefs, or they would face having their children banned from the military, college education, and any civil office. Officials also threatened to have their social welfare benefits revoked. Since these incidents, the three elders have become outcasts, often the object of public scorn. Under constant surveillance by the other villagers, they are no longer able to meet together. In addition, more than thirty other house-church members from the village report experiencing scorn or public shaming due to the treatment of the other three believers.

Various “struggle sessions in disguise” have been rolled out widely. Party and governmental organs, as well as enterprises and public institutions, implemented plans, in which superiors were to monitor the lower-level employees, and colleagues were instructed to monitor each other. Local authorities such as sub-districts and communities set up elderly “Sunset Red Patrols” engaging neighbors to monitor one another. Anti-religious propaganda was disseminated in schools from the elementary to university levels. Teachers were instructed to monitor students, students to monitor teachers, and students to monitor one another.

Thus, religious believers were subject to surveillance – and often discrimination – of the leaders, colleagues, classmates, and neighbors who surrounded them. The masses, all the way down to the level of school children, have inadvertently become the instruments of government oppression. Fengqiao has proven to be both effective, and cost-saving, as the government can rely on the “free” services of citizens rather than paying police to do the oppression.

Hu Ping, the honorary editor-in-chief of Beijing Spring, a monthly magazine dedicated to the promotion of human rights, democracy, and social justice in China, believes that Fengqiao is making a comeback now for a very specific reason. As he sees it, this is an effort on behalf of the Party to strengthen its control during a high-risk time. The Chinese economy is declining, public criticism is increasing, and traditional methods of maintaining social stability are getting more expensive. In these circumstances, Xi Jinping has taken a renewed interest in the Mao-era method.

In this latest version of Fengqiao, religions themselves have been turned against each other to control society and suppress religion. For example, the CCP has incited the government-controlled Three-Self Church to fight against both house churches and some new religious movements that the CCP opposes.

For example, on May 14, in the southeastern coastal province of Fujian, the provincial and municipal Religious Affairs Bureaus convened a five-day conference. At the conference, officials pressured 36 local Three-Self church leaders to collaborate with the government in an effort to clamp down on house churches and religious movements, especially The Church of Almighty God (CAG). The conference stated that, because of CAG’s rapid growth, it was necessary for the government to cooperate with religious groups to suppress it.

During the afternoon when the group met to discuss these issues, every participant was forced to state his or her opinion on the CAG, putting him or her on the record. Authorities then instructed church leaders how to report and track a known member of the CAG. Leaders were also told that anyone who knowingly failed to report a CAG member would be considered equally as guilty as the CAG believer.

The implementation of this policy in Gutian county in Fujian is meant to be a trial run in the larger efforts to suppress the CAG, as is a similar effort, called a “team to beat wolves,” established with 20 members to specifically report house church members.

Even family bonds are exploited in this Maoist effort to turn the citizens into mass informants, a modern adaptation of the 1960s Cultural Revolution model.

During the Cultural Revolution, the “masses fighting against the masses” project reached a peak with children informing on parents, wives betraying husbands, family members betraying one another. Many saw this final stage of the Revolution as the very destruction of moral order.

An internal CCP document, obtained by Bitter Winter and reported on previously, outlines the new effort to turn family members against each other. Entitled Compilation of Special Operation Exemplary Cases, the document orders “town and village officials first to conduct ideological work to convince their (Christian) relatives,” that “the family members persuade their religious relatives” to separate themselves from religion and no longer participate in religious activities. The document further calls for “efforts be focused on reforming the ideologies of missionaries, and their relatives should be the first ones to conduct the ideological work on them.”

Advocates of religious liberty note that being arrested by the police has a temporary and limited effect. But intense pressure from family can last a lifetime and infiltrate every aspect of a Christian’s life. Examples of the pressure brought to bear on, and through, families, are heartbreaking.

Take, for example, an incident in Nanjing. Between April and May, municipal authorities launched a city-wide propaganda campaign against the CAG, which included a 500 to 5,000 RMB reward for those who report CAG members. Again, those failing to report a CAG member of their family would be considered liable.

According to CAG believer Li Xiulan (a pseudonym), when her husband saw the government’s notice, he immediately forced her to abandon the church. “The notice is clear,” he said. “If one family member believes in God, the whole family is guilty. Afterwards, their children will not be able to go to college, join the military, or find a job. Not only that, but if they get caught, they would be put in jail for three years.” (A reference to the minimum term in prison for being active in a xie jiao “heterodox teachings” organization, as per the Article 300 of the Chinese Criminal Code).

As a young man, Li Xiulan’s husband was persecuted in the Cultural Revolution, and all his brothers and sisters were implicated. Now he still harbors that fear in his heart. He believes that “the Communist Party does whatever it wants; no matter how beneficial faith in God is, one can’t have that faith.”

According to another CAG member, several of the believer’s relatives had pressured him to abandon the church because of the influence of the government’s propaganda. Some elderly Christians are also being refused support from relatives because the relatives fear the punishment that would come with supporting religious family members.

The Cultural Revolution left terror and misery in its wake 50 years ago. A new cultural revolution, pitting brother against brother and believer against believer, is threatening to bury freedom of religion and freedom of conscience in 21st century China.

Source: Bitter Winter / Jiang Tao